MODERN CELTS, Kelted Today, Celtiaid heddiw,

Ceilteach an-diugh, Ceiltigh inniu:

Let’s start with the languages

The translation into the four main Celtic languages shows both differences and obvious kinship, just as you would find when comparing the equivalents in Romance languages. Keep in mind that dialectal varieties often show even greater similarities than the official and standardized forms. For instance, standard Breton says enez for island, while Irish says inis. However, in central and southern Brittany, we also say inis.

Standard Breton says Amzer, Gaelic says Aimsir. But Southern Breton says Amzir. Leun is the standard Breton for full, Gaelic says Lán. But local Breton also says Lan. We find tons of similar cases. For height, standard Irish says Cnoc, while Donegal says Croc. In Breton, we also have both forms Kenec’h and Krec’h.

Orthographies also give the impression of differences: these are merely arbitrary, even temporary conventions. Other apparent differences exist only due to the different cases in Gaelic declensions. Ti in Breton becomes teach or tí in Irish. Yann in Breton becomes Sean in Gaelic, except that in another case, Sean becomes Ian or Iain. The same goes for the elbow: ilin in Breton, uileann in Scottish Gaelic, but uilinn in the genitive.

Many examples show that Gaelic is less different from Breton than one might think. We have at least 3,000 common everyday words (a first glance at a dictionary reveals many examples).

CELTS TODAY

Let’s start with languages

Translation into the four major Celtic languages shows both differences and obvious similarities, just as you would compare the equivalent in Romance languages. Without losing sight of the fact that dialect varieties often show even greater similarities than official and standardized forms. For example, official Breton says enez for island, Irish says inis. But, in central and southern Brittany, we really say inis.

The official Breton says Amzer, the Gaelic Aimsir. But the Breton Vannetais says Amzir. Leun is the official Breton for full, the Gaelic says Lán. But the local Breton also says Lan. There are tons of similar cases. For height, the official Irish says Cnoc, when Donegal says Croc. In Breton, we also have the two forms Kenec’h and Krec’h.

The spellings also give the impression of differences: they are only arbitrary, even provisional, conventions. Other apparent differences only exist across the different cases of Gaelic declensions. Ti in Breton becomes teach or tí in Irish. Yann in Breton becomes Sean in Gaelic, except that in another case, Sean becomes Ian or Iain. Same thing for the elbow: in Breton ilin, in Scottish Gaelic uileann, but uilinn in the genitive case.

Numerous cases show that Gaelic is less different from Breton than we think. We have at least 3000 common everyday words (a first look in a dictionary shows many examples).

The Celtic language family is comparable to the Romance languages.

A French speaker can partially understand Latin without having studied it, just as they can half-understand Italian. I understand ancient Celtic in the same way (a term I take the liberty of preferring to Proto-history).

There is clearly a lineage. And one often hears clumsily (with an ethnic connotation) the phrase “we, the Latin nation” as opposed to “them, the Anglo-Saxons.” This is particularly shocking in Brittany… And shocking that it doesn’t shock more people.

Celtic languages share thousands of everyday words (25 to 50% of the vocabulary), with additional words from English, French, and Latin. Anecdotally, it’s not uncommon for a Gaelic word to resemble French more closely than its Breton equivalent.

Differences do exist (otherwise, we wouldn’t speak of languages in the plural), but the syntaxes and grammars are similar enough, distinguishing this family from other Indo-European languages.

The Celtic language family is comparable to that of Latin languages.

A French speaker partially understands Latin, without having studied it, just as he half understands an Italian. I understand the Celtic of Antiquity in the same way (a term that I take the liberty of preferring to Proto-history).

We clearly see a connection. And we hear it said every day awkwardly (an ethnic remark) “we, the Latin nation” as opposed to “them, the Anglo-Saxons”. It’s particularly shocking in Brittany…And shocking that it’s not shocking.

Celtic languages share thousands of common words (25 to 50% of the vocabulary) to which English, French and Latin words are added everywhere. Anecdote: it is not uncommon for a Gaelic word to resemble French more than its Breton equivalent.

The differences exist (otherwise we would not speak of languages in the plural), but the syntaxes and grammars are quite close, distinguishing this family from other Indo-European languages.

The chicken and the egg: languages are the product of thought patterns, and vice versa.

When a person speaks Breton, their thoughts are shaped by Breton thinking. And this can be said more broadly for Celtic thought and languages: different concepts, sometimes less ambiguous (e.g., identities), sentences with variable word order, where most often the subject is secondary to the action, the individual is subordinated to the collective, having is dominated by being, the masculine is slightly less dominant (DEN), the initial consonant is mutable, colors are perceived differently, and gender may be reversed compared to French.

We speak and write within a family of languages and culture where everything is fluid, like water, life, and reality.

Geography

You’re lucky if you hear these languages spoken. But (unless you’re visually impaired), we also have eyes to see.

The chicken and the egg: languages are the product of forms of thought, and vice versa.

When speaking Breton, an individual’s thinking is guided by Breton thinking. And we can say this more broadly for Celtic thought and languages: different concepts, sometimes less ambiguous (e.g. identities), sentences, whose order is variable, where, most often, the subject is forgotten for the benefit of action, the subordination of the individual for the benefit of the collective, having it dominated by being, the masculine a little less the leader (DEN), the inconstant initial, the colors perceived differently, the gender can be reversed compared to French.

We speak and write within a family of languages and culture where everything is moving, like water, life and reality.

Geography

You need luck to hear these languages. But (apart from the unlucky visually impaired) we also have eyes to see.

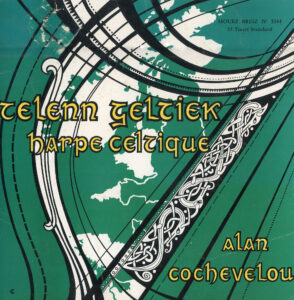

Here is my first album (1964), with the new cover I designed in 1966. It incorporates the map of the six Celtic-speaking nations.

Here, my first album (1964), with the new cover that I designed in 1966. This includes the map of the six Celtic-speaking nations.

First, we see an archipelago of islands and peninsulas.

Their inhabitants are, above all, immersed in this marriage between land and sea (climate, activities, gestures, food), with the ocean and the Hercynian ground shaping the landscapes and constructions. Whether looking at geography or habitat, who doesn’t see this unity… and who doesn’t see the disparity in the so-called Latin world (with or without quotation marks), from Wallonia to Sicily ?

Housing

A brief reflection on housing: my surprise (not really) at never finding any scientific statistics on the types of houses in the six countries. How can this significant omission be explained, linked to psychology and education ? And very few architects seem to have noticed that the so-called Breton house, the most common and characteristic (with its gable-end chimneys and roof ridge, its blind or semi-blind gables, like the rear), should more accurately be called Celtic. It is an absolute majority in Scotland and Brittany, a relative one in Wales and Ireland. The Celtic house is more often white (West Ireland, West Scotland, West and South Brittany), except for locally varied colors, or exposed stone (North coast and inland Brittany, East and inland Scotland, East and inland Ireland). And to complete the picture, we see more ocher-colored houses appearing in East Brittany, East Ireland, and East Scotland (to be checked for Wales).

We first contemplate an archipelago of islands and peninsulas.

Its inhabitants are, above all, bathed in these land-sea marriages (climate, activities, gestures, food), the ocean and the Hercynian soil creating landscapes and constructions. When it comes to geography or habitat, who does not see this unity…and who does not see the disparity of the so-called Latin world (with or without quotation marks), from Wallonia to Sicily?

The habitat

A little thought on housing: my astonishment (not so much) at never having found any scientific statistics on the types of houses in the six countries. How can we explain this significant oversight, linked to psychology and education? And a limited number of architects seem to have noticed that the so-called Breton house, the most common and characteristic (with its gabled and ridge chimneys, with blind or semi-blind gables, like the rear) must be more aptly described as Celtic . In absolute majority in Scotland and Brittany, relative in Wales and Ireland, the Celtic house is more often white (West Ireland, West Scotland, West and South Brittany), except for locally diversified colors, or in exposed stone (north coast and interior Brittany). , East and interior Scotland, East and interior Ireland And, to complete it all, we are seeing more ocher houses appear in East Brittany, East Ireland, East Scotland (to be checked for Wales).

Publications on this subject are hard to come by. This fact also raises questions.

Strengthening our ties

Today, it is essential to strengthen ties, both culturally and economically.

As modern Celtic nations in Northwest Europe, we share much of what doesn’t come from English and French influences. Unfortunately, it is undeniable that these strong influences largely erase the cultural uniqueness of our countries. That what remains of it is the great treasure to be safeguarded has always been obvious to me.

This obviousness is not understood by some : I suppose it shakes comfortable, established philosophical and political positions, or, to some extent, scientific ones. Questioning these, after years of education, training, and recognition, is difficult to accept.

This Breton culture, these Celtic cultures, are not just treasures for our direct heirs, but the heritage of all humanity. They are not relics, but an infinite creative potential. They encompass all fields (philosophy and science included).

It is very difficult to find publications that are interested in this. This fact is also striking.

Strengthen our bonds

It is today that it is essential to strengthen ties, both for culture and for the economy.

Modern Celtic nations, in the European North-West, we share much of what does not come from English and French impregnations. It is unfortunately indisputable that these strong influences largely erase the originality of our countries on a cultural level. That what remains is the great treasure to be saved has always been obvious to me.

This evidence is not understood by some: I suppose that it shakes comfortable established positions, philosophical and political, or, to a certain point, scientific. The challenges, after years of education, training, recognition, are difficult to accept.

This Breton culture, these Celtic cultures, it is not only a treasure for our direct heirs, it is the heritage of all humanity. It is not a relic, but infinite creative potential. It encompasses all fields (philosophy and science included).

Paris (or the various French powers and reflexes) had a project that destroyed part of humanity’s heritage and potential, depriving it of this richness. After much “insistence,” the French state had to accept that palliative care could be administered. This remains the case when viewed objectively and realistically. Will the many problems we face together help people understand how ridiculous it is not to let us live the Brittany that the majority of its inhabitants dream of

Paris (or the various French powers and reflexes) had a project which destroyed part of the heritage and potential of humanity, defrauding it of this wealth. After so much “insistence”, the French state had to accept that palliative care could be provided. This still remains the case if we look at things objectively and realistically. Will the multiple problems that we have to face together not make us understand the ridiculousness of not letting us live the Brittany that the majority of its inhabitants dream of?